Native American History & Culture in New Mexico

History of the Mimbres Indians

Long before Columbus and Coronado there were people living in southwestern New Mexico. Hunting and grinding artifacts, pottery and beads dating back 10,000 years have been found near the ranch. The region was home to the Mimbres, an advanced pre-historic Indian culture. Highly artistic, they are known for their exquisite black-on-white pottery featuring nature motifs. The Mimbres made their homes farming and hunting along the Gila River, living in pit houses, shallow caves and small cliff dwellings. Earlier Indian cultures most certainly lived in the area. Limited evidence of hunting by the earliest inhabitants (9500-6000 BC) has been found in several highland areas. Widespread evidence of the Archaic Culture, which is considered part of the Cochise Culture dating from 6000 BC to 300 AD, has been found in the region.

The Mimbres people are an enigma to archeologists, because they can only speculate about their beginnings and especially about their ultimate fate. Archeologists believe the Mimbres culture evolved from the Mogollon culture, which itself possibly evolved from the Anasazi and/or the Hohokam cultures. During the Mimbres phase, the move was made from pit houses, to semi-pit houses, and then to above ground pueblos. The dead were often buried under the floor inside the house, with a pot covering their head. The big puzzle is what happened to the Mimbres people. It is speculated that the original Mimbres moved away, and were integrated into other cultures, possibly to the south.

It is not likely that they were driven from the area by warfare, as evidence points to an exodus extending over a period of years. It is possible that the Mimbres exhausted the natural resources of the area, and were forced to relocate, or were forced to move due to drought.

Mimbres pottery is the most famous artifact of the Mimbres culture. Pottery was made in plain and corrugated brown clay, polychrome, black and red, and the famous black and white. The black and white pottery usually depicted animals encountered in daily life, daily routines, or geometric designs. Cranes, turkeys, fish, mosquitoes or hummingbirds, small mammals, and humans often grace Mimbres pottery. The expertise of the Mimbres potters is considered superior to that of any other Native American potters. A characteristic of pots found associated with a burial is that of the “kill hole”. A piece was broken out of the bottom of the pot. It is postulated that this might have been to release the soul of the deceased.

Nearby, there are several privately protected Mimbres pictographs, cave dwellings and pit houses dating from 200 to 1150 AD. Somewhere in the early 1300s the Mimbres people suddenly left the area. Some speculate their numbers grew to a point beyond the carrying capacity of the area and the culture collapsed. Disease, drought and war were also factors. They were gone by 1400 when the last wave of Asian immigrants entered the areas from the north, destined to form two distinct modern tribes: The Apache and the Navajo.

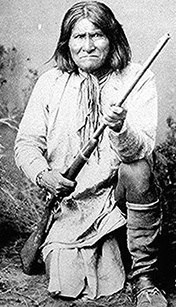

“I was warmed by the sun, rocked by the winds and sheltered by the trees.” -Geronimo

Geronimo {jur-ahn’-i-moh}, or Goyathlay (“one who yawns”), was born in 1829 in what is now western New Mexico, but was then still Mexican territory. He was a Bedonkohe Apache (grandson of Mahko) by birth and a Net’na during his youth and early manhood. His wife, his brother-in-law Juh, his cousin Ishton, and Asa Daklugie were members of the Nednhi band of the Chiricahua Apache.

He was reportedly given the name Geronimo by Mexican soldiers, although few agree as to why. As leader of the Apaches at Arispe in Sonora, he performed such daring feats that the Mexicans singled him out with the sobriquet Geronimo (Spanish for “Jerome”). Some attributed his numerous raiding successes to powers conferred by supernatural beings, including a reputed invulnerability to bullets.

Geronimo’s war career was linked with that of his brother-in-law, Juh, a Chiricahua chief. Although he was not a hereditary leader, Geronimo appeared so to outsiders because he often acted as spokesman for Juh, who had a speech impediment.

Geronimo was the leader of the last American Indian fighting force formally to capitulate to the United States. Because he fought against such daunting odds and held out the longest, he became the most famous Apache of all. To the pioneers and settlers of Arizona and New Mexico, he was a bloody-handed murderer and this image endured until the second half of this century.

To the Apaches, Geronimo embodied the very essence of the Apache values- aggressiveness and courage in the face of difficulty. These qualities inspired fear in the settlers of Arizona and New Mexico. The Chiricahuas were mostly migratory following the seasons, hunting and farming. When food was scarce, it was the custom to raid neighboring tribes. Raids and vengeance were an honorable way of life among the tribes of this region

By the time American settlers began arriving in the area, the Spanish had become entrenched in the area. They were always looking for Indian slaves and Christian converts. One of the most pivotal moments in Geronimo’s life was in 1858 when he returned home from a trading excursion into Mexico. He found his wife, his mother and his three young children murdered by Spanish troops from Mexico. This reportedly caused him to have such a hatred of the whites that he vowed to kill as many as he could. From that day on he took every opportunity he could to terrorize Mexican settlements and soon after this incident he received his power, which came to him in visions. Geronimo was never a chief, but a medicine man, a seer and a spiritual and intellectual leader both in and out of battle. The Apache chiefs depended on his wisdom.

When the Chiricahua were forcibly removed (1876) to arid land at San Carlos, in eastern Arizona, Geronimo fled with a band of followers into Mexico. He was soon arrested and returned to the new reservation. For the remainder of the 1870s, he and Juh led a quiet life on the reservation, but with the slaying of an Apache prophet in 1881, they returned to full-time activities from a secret camp in the Sierra Madre Mountains.

In 1875 all Apaches west of the Rio Grande were ordered to the San Carlos Reservation. Geronimo escaped from the reservation three times and although he surrendered, he always managed to avoid capture. In 1876, the U.S. Army tried to move the Chiricahuas onto a reservation, but Geronimo fled to Mexico eluding the troops for over a decade. Sensationalized press reports exaggerated Geronimo’s activities, making him the most feared and infamous Apache. The last few months of the campaign required over 5,000 soldiers, one-quarter of the entire Army, and 500 scouts, and perhaps up to 3,000 Mexican soldiers to track down Geronimo and his band.

In May 1882, Apache scouts working for the U.S. army surprised Geronimo in his mountain sanctuary, and he agreed to return with his people to the reservation. After a year of farming, the sudden arrest and imprisonment of the Apache warrior Ka-ya-ten-nae, together with rumors of impending trials and hangings, prompted Geronimo to flee on May 17, 1885, with 35 warriors and 109 women, children and youths. In January 1886, Apache scouts penetrated Juh’s seemingly impregnable hideout. This action induced Geronimo to surrender (Mar. 25, 1886) to Gen. George Crook. Geronimo later fled but finally surrendered to Gen. Nelson MILES on Sept. 4, 1886. The government breached its agreement and transported Geronimo and nearly 450 Apache men, women, and children to Florida for confinement in Forts Marion and Pickens. In 1894 they were removed to Fort Sill in Oklahoma. Geronimo became a rancher, appeared (1904) at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, sold Geronimo souvenirs, and rode in President Theodore Roosevelt’s 1905 inaugural parade.

Geronimo’s final surrender in 1886 was the last significant Indian guerrilla action in the United States. At the end, his group consisted of only 16 warriors, 12 women, and 6 children. Upon their surrender, Geronimo and over 300 of his fellow Chiricahuas were shipped to Fort Marion, Florida. One year later many of them were relocated to the Mt. Vernon barracks in Alabama, where about one quarter died from tuberculosis and other diseases. Geronimo died on Feb. 17, 1909, a prisoner of war, unable to return to his homeland. He was buried in the Apache cemetery in Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

Story has it that Geronimo and his band stole some pretty good mares from this and surrounding ranches, killing the colts to keep them from following. A group of local ranchers took chase, following the trail to the base of the mountains near Turkey Creek where they found a mare with her throat cut, still bleeding out. Needless to say, the ranchers decided right then the horses weren’t worth THAT much, after all! All turned about and headed back for home. Only 130 years have passed since Geronimo surrendered, permitting miners and homesteaders to explore and settle the Gila-Bear Creek region without fear of Indian attack.

Explore the history and Native American culture when you stay at Geronimo Trail Guest Ranch!

COMPARE EXPERIENCES

| ALL-INCLUSIVE | CREATE YOUR OWN | CABIN RENTAL | |

| Cabin | YES | YES | YES |

| Horseback Riding | YES | YES | NO |

| Guided Hiking & History | YES | YES | NO |

| Meals | YES | NO ( Request a Chef ) | NO |

| Dates Offered | mid-March thru mid-June | mid-June thru December; February | Year-Round |

| Length of Stay Offered | 1 – 6 Nights | 1 – 6 Nights | 1 or more Nights |

| Price | From $599 per person, per night | Ala Carte | From $149 – $299 per night |

LEARN MORE: Click on the package titles above!